|

Harnessing

the Power of Human Ingenuity

Steven Wille & Dr.

James Rairdon

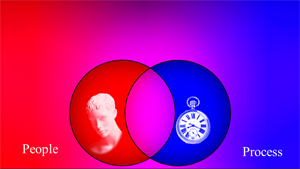

To lead a

great organization you need strength in two critical areas:

people and

process.

Great people doing great things. That was the conventional wisdom

in the 20th century, but many excellent companies from

that era did not make into to the 21st century. Today,

we need more. We need innovation and human ingenuity. Things are

changing fast and if we don't keep up our companies, and our

careers, are likely to falter and fade quickly. Back in the

mid-nineteen hundreds, companies lasted an average of 61 years on

the Standard & Poor 500 list, which was longer than a normal

career. Today, the average is 18 years. How can you survive and

thrive? To lead a

great organization you need strength in two critical areas:

people and

process.

Great people doing great things. That was the conventional wisdom

in the 20th century, but many excellent companies from

that era did not make into to the 21st century. Today,

we need more. We need innovation and human ingenuity. Things are

changing fast and if we don't keep up our companies, and our

careers, are likely to falter and fade quickly. Back in the

mid-nineteen hundreds, companies lasted an average of 61 years on

the Standard & Poor 500 list, which was longer than a normal

career. Today, the average is 18 years. How can you survive and

thrive?

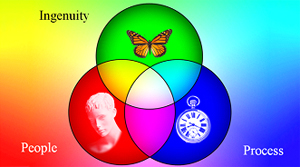

We are not

proposing that the old management leadership formulas should be

discarded. We are saying you need all three,

people,

process,

and human

ingenuity.

It is like the three colors in your television coming together to

make white light. It simply cannot be done with just two colors.

The three color LED lights in your television are red, blue and

green. We will use these three colors to represent the three

critical skills for management leaders, with red representing

people, blue representing process, and green representing human

ingenuity. All three are needed in appropriate quantities to create

the full picture.

Let’s start

with human ingenuity, the green in our model. You notice there's a

butterfly in the graphic, representing the

butterfly effect. Small changes in

starting conditions can result in big changes in outcome. Because

of the butterfly effect we will never be able predict the outcome

from a complex system. The butterfly effect came from Edward

Lorenz, who is known as the father of chaos theory. He wrote a paper

in 1972,

Predictability, does the flap of a butterfly's wing in Brazil set

off a tornado in Texas?"

There is an interesting story behind this. In 1961,

he and a group of meteorologists were using computers to predict the

weather. Digital computers were relatively new in 1961 and they did

not have graphical monitors with pictures back then. They had

printouts with numbers on paper that represented quantifiable data,

such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and other variables. Let’s start

with human ingenuity, the green in our model. You notice there's a

butterfly in the graphic, representing the

butterfly effect. Small changes in

starting conditions can result in big changes in outcome. Because

of the butterfly effect we will never be able predict the outcome

from a complex system. The butterfly effect came from Edward

Lorenz, who is known as the father of chaos theory. He wrote a paper

in 1972,

Predictability, does the flap of a butterfly's wing in Brazil set

off a tornado in Texas?"

There is an interesting story behind this. In 1961,

he and a group of meteorologists were using computers to predict the

weather. Digital computers were relatively new in 1961 and they did

not have graphical monitors with pictures back then. They had

printouts with numbers on paper that represented quantifiable data,

such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and other variables.

One day

Lorenz wanted to extend a forecast, so he keyed in the printed

numbers from the first run, ran the model, and was surprised by the

results. For the first few days, the weather was similar to the

first run, but 30 days out, it was completely different.

At

first he thought that there must be a vacuum tube broken in his

computer. Then he realized the printout was rounded to three decimal

points, but the computer memory was rounded to six decimal points. A

difference in temperature of less than one-one thousands of a degree

in his model changed the outcome dramatically 30 days out. Right

then, he knew we would never predict the weather 30 days out. Here

we are 50 years later, and we still can't. He was right. He spent

the rest of his life looking at non-linear equations and at problems

that can't be solved in a traditional linear way, but exhibit

predictable patterns and possibilities. Today, chaos science, also

known as complexity theory, is recognized as the way the natural

world works. So many variables come together at one time it is

absurd to attribute any natural event to a single factor. It is the

interaction of variables that delivers the outcome.

To see human ingenuity emerge from complexity, we are

going to look at history. Consider ancient Athens, the birthplace of

what we know as western thought, including democracy, philosophy,

and the scientific method. Where did this human ingenuity come from

in this small city on the Mediterranean two thousand five hundred

years ago? When we think of Athens we often picture the temples on

the acropolis, but that is not where the human ingenuity emerged. It

emerged from the city. The Acropolis, with its temples, is on the

hill. The people were in the city. Here is a recent picture of

Athens, the very same streets where Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and

so many other great thinkers roamed. There was an unusual quantity

of highly intelligent people along with political and economic

condition where they could think, debate, write, and do cool things.

They changed the world. To see human ingenuity emerge from complexity, we are

going to look at history. Consider ancient Athens, the birthplace of

what we know as western thought, including democracy, philosophy,

and the scientific method. Where did this human ingenuity come from

in this small city on the Mediterranean two thousand five hundred

years ago? When we think of Athens we often picture the temples on

the acropolis, but that is not where the human ingenuity emerged. It

emerged from the city. The Acropolis, with its temples, is on the

hill. The people were in the city. Here is a recent picture of

Athens, the very same streets where Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and

so many other great thinkers roamed. There was an unusual quantity

of highly intelligent people along with political and economic

condition where they could think, debate, write, and do cool things.

They changed the world.

At many times and places in history human ingenuity

emerged to change the world. Consider William Shakespeare. Some

people say he couldn't have written the works of Shakespeare. It was

too good. There must have been more to the story. He lived in

Elizabethan London when poetry and plays were valued. There were no

copyright laws, so writers could borrow from one another. Every

iteration got better. It was because Shakespeare lived in London in

the Elizabethan age that he could interact with other great

writers. From this place and time emerged some of the greatest

literature in the English language.

There is a modern day ancient Athens and Elizabethan

London where ideas are emerging at an incredible rate. Consider the

Silicon Valley in California. Because it is a concentrated area

with smart people packed together, unintentional collaboration leads

to new ideas. New products emerge. Marissa Mayer, a long time

Google employee was hired by Yahoo to be CEO and bring more of the

Google culture to Yahoo. One of the first things she did was

announce the end of telecommuting so that people would be together.

She recognized that people may be more productive when working

alone, but she was willing to give up productivity to get more

collaboration.

The Gallup Business Journal reported that according

to their studies when employees spend no time working remotely, 28%

were engaged in their work and 20% were disengaged. Gallup found

that by spending 20% of their time working remotely, employee

engagement went up to 35% and disengagement down to 12%. Above 20%

working remotely, the engagement and disengagement trended

backwards. This suggests there is a human need to work alone and a

human need to interact in the same space. In other words, doing

both is better than one to the exclusion of the other. Going back

to the red, blue, green model, one color to the exclusion of the

others throws the picture off color. We need the green of

collaboration that lets human ingenuity emerge, and we need the blue

of routine work that is best done working alone.

This leads us to the blue in our model, represented

by a watch. The watch maker makes the watch, sells it, and never

visits the customer again. This is possible because of the quality

craftsmanship that goes into building a machine that operates in a

controlled and predictable way. Extending the watchmaker model to

the business world, we need organizations that operate in controlled

and predicable ways. Repeatable processes and best practices are

key to achieving this.

At one time,

made in

Japan inferred low

quality products that would fall apart quickly. Today,

made in

Japan

infers high quality. What changed? Much of the credit for the

transformation goes to W. Edwards Deming who emphasized statistical

process controls. In the late 20th century when American companies

were falling behind in quality, Deming returned to America and

helped create a quality awakening. Today, American companies

compete globally with quality products.

The great American productivity that emerged in the

early 20th century can be traced to the work of Frederick Taylor who

is recognized as the father of scientific management. Prior to this

time labor was cheap and not much attention was paid to worker

productivity. Who cared about immigrants, serfs, peasants, or

slaves, as long as the work got done? Taylor quantified the value

of labor. He walked around with a stopwatch to see how long any

task might take, and then he looked for a faster way to do that

task. He also engineered the tools to aid productivity. For

example, he optimize the size and shape of a shovel, making it

appropriate for the material to be shoveled. A worker should go

home tired but not exhausted. Peter Drucker, another great

management thinker of the 20th century said of Taylor, “On Taylor's

scientific management rest, above all, the tremendous surge of

affluence in the last 75 years which has lifted the working masses

in the developed countries well above any level recorded before even

for the well-to-do." Scientific management changed the world. The great American productivity that emerged in the

early 20th century can be traced to the work of Frederick Taylor who

is recognized as the father of scientific management. Prior to this

time labor was cheap and not much attention was paid to worker

productivity. Who cared about immigrants, serfs, peasants, or

slaves, as long as the work got done? Taylor quantified the value

of labor. He walked around with a stopwatch to see how long any

task might take, and then he looked for a faster way to do that

task. He also engineered the tools to aid productivity. For

example, he optimize the size and shape of a shovel, making it

appropriate for the material to be shoveled. A worker should go

home tired but not exhausted. Peter Drucker, another great

management thinker of the 20th century said of Taylor, “On Taylor's

scientific management rest, above all, the tremendous surge of

affluence in the last 75 years which has lifted the working masses

in the developed countries well above any level recorded before even

for the well-to-do." Scientific management changed the world.

One of the greatest scientific management experiments

of all time, was at the Western Electric Hawthorne plant, just south

of Chicago. In the 1920s, there were 40,000 people working in this

plant where telephone equipment was made. The telephone was to the

early 20th century what the internet is to the 21st century. In

today's dollars, the annual output of this factory was 3.7 billion

dollars' worth of goods. It was a great place to test scientific

management because a small gain in productivity would lead to a

large gain in profit. That thinking led to the illumination

experiments. Before starting the experiment, productivity was

measured to create a baseline at a specific level of light. At the

time, factories were lit by natural light coming in through

windows. The question at hand was the potential value of increasing

the illumination through electric lighting. Illumination was

doubled and productivity went up. It was doubled again and

productivity increased. To be a valid experiment there had to be a

negative test. The lights were dimmed. Productivity remained high.

They had to bring the lighting down to 0.06 foot candles, the level

of moon light, before productivity went below baseline. This

experimenting ran for two and a half years.

The Hawthorne plant was still operating in 1975 when

the director of corporate planning for AT&T, Henry Boettinger, said,

"The experimenters at the Hawthorne plant did not discover what they

set out to find and the researchers had sense enough to recognize

what they had found." A whole new world opened up because of this

experiment. That takes us to the red part of our model, the people

side. A factory is more than a building with equipment, processes

and procedures. Human beings do the work. Human systems are

complex and it is difficult to isolate one factor, such as lighting,

and say it will lead to higher productivity. The Hawthorne plant was still operating in 1975 when

the director of corporate planning for AT&T, Henry Boettinger, said,

"The experimenters at the Hawthorne plant did not discover what they

set out to find and the researchers had sense enough to recognize

what they had found." A whole new world opened up because of this

experiment. That takes us to the red part of our model, the people

side. A factory is more than a building with equipment, processes

and procedures. Human beings do the work. Human systems are

complex and it is difficult to isolate one factor, such as lighting,

and say it will lead to higher productivity.

For next six years the human factor was studied. A

relay assembly test room was set up so the output from a team could

be accurately measured. Working conditions were modified in many

ways, such as work hours, breaks, and earning more pay for more work

output. In addition to this, over 20,000 workers were interviewed

personally in open ended sessions conducted by trained interviewers

who were focused on how people really felt about their jobs.

Aaccording to the testers, as summarized by Elton

Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger, many human factors come together, but

one thing that stood out. The supervisor's method was the single

most important variable. That launched the whole business of

management training with a focus on the human relations side of

management, in addition to the process side of management. The

Hawthorne phenomena is much bigger than a single interpretation of

what caused the increase in productivity. It is the complex

interaction of many factors coming together.

This pivotal experiment was nearly a hudred years

ago. Is it relevant to the 21st century? In 1994,

Discover

Magazine

reported an odd occurrence. Some teams in a call center were more

productive than other teams, even though all teams were essentially

the same in human skills and experience with the same working

conditions. An outside experimenter focusing on human interaction

observed that the teams that took their breaks together were fifteen

to twenty percent more productive then teams that took staggered

breaks.

A retired engineer from Hewlett Packard told us that

back in the 1960s, when HP was the great innovative company, every

mid-morning a coffee cart would roll in with free donuts and coffee.

Engineers quit working to stand in line for donuts and coffee. How

many companies roll in a cart with free donuts and coffee 10:30

every morning so that they can get some better collaboration? It

may seem like a waste of time, but fifteen to twenty percent more

productivity is not something to be ignored.

It would be fair to say that management practice in

the 20th century evolved to encompass both people and process. It

also would be fair to say that the massive corporate productivity

and quality gains of the 20th century were related to these

enlightened management practices. Since then the world has changed

and 20th

century solutions many not be sufficient for 21st century problems.

We live in a Wiki world. Wiki is Hawaiin for quick. Rod Collins,

author of Wiki Management, says, “Nobody is smarter and everybody

and nobody is faster than everybody.” People around the globe are

working simultaneously on new opportunities. The old hierarchy and

bureaucracy from the 20th century cannot keep up. It is dead. The

authors of this paper agree with Collins when examining corporations

under the green light in our model, but we maintain the hierarchy is

alive and well under the blue light of process control and quality

operations. In other words, we are proponents of red, blue, and

green light making white light, and that is the place to be in the

21st century.

Three Proposals

The historical support for this three color model for

management leadership is interesting, but it does not tell us what

to do in the future. Therefore, we offer three color proposals.

You won't find these in any book. We made them up, but they're

based on the idea that all three dimensions are useful, and one to

the exclusion to the others is a mistake. The purpose of our

proposal is to get you into three color thinking in every

interaction. We will look at three situations and offer three

different ways of seeing these situations.

Show

Respect

Under the blue light, showing respect is to respect

the position. The chair represents the authority of the person

sitting in the chair. What do you do when a person of authority

tells you to do something? You do it, unless it's illegal or

unethical. If you cannot get this right you will not last long in

the organization. Under the red light it is a whole different

picture. This is where you respect the person, not the position.

The red and blue are in direct opposition. Do I respect the person

or the position? The answer is both. This was learned in the 20th

century. Most organizational people have figured out how to do

both. In the 21st century equality and position are still

important, but a third dimension has emerged. The green light has a

libertarian tint to it. We respect the individual and we do not

treat everyone the same. We do not say, “If we do it for you, we

have to do it for everyone.” Instead, we look at individual

opportunities. That is the only way to allow human ingenuity to

emerge. What if you had Aristotle working for you, and Aristotle

did not feel like doing it your way? Would you say, "If we do it for

you, Aristotle, we have to do it for everybody." There are many

Aristotles working at your place right now. We have a highly

educated workforce. Many workers do not mind trying new ideas that

may or may not work. Are you shutting them down with simplistic

rules that apply to everybody? We have no trouble giving the people

in the hierarchy special privilege. Is it unreasonable to give

special privilege to the highly ingenious people?

Get

Feedback

Under the blue light, numbers are the key to quality

and process improvement. A feedback system with objective

measurements tells you where you are out of compliance and gives an

opportunity for corrective action. Measurements work is sports,

too. When you keep score you focus on things that affect the

score. In general, you get what you measure.

Under the red light, feedback is not measurable. It

is about how people feel. The response is not corrective action,

but rather, empathy. Only through a non-directive, non-judgmental,

empathetic response do you get people to open up and tell you what

they really think. This kind of feedback is just as valuable as the

numbers, but it is different and serves a different purpose. You

need both, all the time.

The type of feedback you get under the green light

can be a challenge for management leaders because the feedback is

slower. You wait and see. How long does it take to solve a

difficult problem? No one knows because it has not yet been

solved. There are no simple answers for complex problems.

Admitting you do not know everything is a mark of maturity.

Eventually you might know, and based on that longer term feedback

you can make appropriate decisions, but anything quicker can be

misguided.

Get

Engaged

Employee engagement is a hot topic. We want people

to be all they can be. That is good for the person and good for the

organization. Disengagement serves no one. Our third proposal is

about maximizing employee engagement.

Under the blue light it is all about being a part of

something bigger and making a meaningful contribution to the mission

of the organization. We set goals and tie them to meaningful

organizational goals. We also delegate meaningful work to people as

they progress in their careers. The reward for a job well done is

more work and more responsibility.

Under the red light it is about feelings. Even if a

person is making a meaningful contribution, if there is no

indication that the work is valued, why bother? Pay for performance

without an equal dose of genuine gratitude is the fast path to

disengagement. Human beings can be so complicated and demanding.

Even with a meaningful contribution and feeling of

value, there is a limit on what a person can do. The green light

symbolizes the multitude of other things required for a person to be

enabled to be fully engaged. Enablement includes skills training

and general support, plus the freedom to act. It also includes room

for failure and trying again.

These three proposals are intended as a general guide

for thinking in three dimension and seeing things under a different

light. We all have our personal filters and selective

color-blindness. Only by taking the time to remove the filters and

see the situation differently can we manage and lead when the world

keeps changing at a rapid pace.

___________________________________

Comments and

questions are welcome:

steve.wille@ColorfulLeadership.INFO

___________________________________

Authors:

JAMES L.

RAIRDON, DM, FLMI

National American University

The Harold Buckingham Graduate School of Business

1325 S. Colorado

Blvd Suite 100

Denver, Colorado, 80222

jrairdon@national.edu

STEVEN F.

WILLE, PMP, MBA

Rocky Mountain Information Management Association

1790 E. Easter Ave. Centennial, CO 80122

swille@rmima.org\

___________________________________

Sources:

Boettinger, H. M.

(1975). The learning of doing: Hawthorne in historical perspective.

In E. L. Cass & F. G. Zimmer (Eds.). Man and Work in Society (pp.

259-265). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

Gleick, J.

(butterfly effect)

(1987). Chaos: Making a new science. New York: Penguin Books.

Gallup Business Journal

March 13, 2014

Can

people collaborate effectively while working Remotely?

Drucker, Peter:

181 (1974). Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. New

York: Harper & Row. ISBN 1-4128-0627-5

Lehrer, Jonah (Shakespeare

– only in 16th Century London)

(2012-03-19). Imagine: How Creativity Works (p. 215).

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Kindle Edition.

Marissa Mayer:

Great Place to Work conference

http://fortune.com/2013/04/19/marissa-mayer-breaks-her-silence-on-yahoos-telecommuting-policy/

Roethlisberger, F. J.

(1941). The Hawthorne Experiments. In J. M. Shafritz, J. S. Ott & Y.

S. Jang (Eds.) (2005). Classics of Organization Theory (6th ed.)

(pp. 152-157). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth Publishers.

Roethlisberger, F. J. & Dickson, W. J.

(1939). Management and the worker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Regalado, Antonio

MIT Technololgy

Review September 10, 2013

http://www.technologyreview.com/view/519226/technology-is-wiping-out-companies-faster-than-ever/

Taylor, F. W.

(1911). Scientific management. As found in Taylor, F. W. (1975)

Scientific Management (3rd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press,

Publishers.

Taylor, F. W.

(1903). Shop management. A paper presented to meeting of The

American Society of Mechanical Engineers. As found in Taylor, F. W.

(1975) Scientific Management (3rd ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood

Press, Publishers.

___________________________________

Photographs and

Graphics

Athens Photographs:

Steve Wille Photography

Graphics:

Steve Wille

Historical Photogographs:

Copyright on the Taylor and Hawthorne photographs are unknown.

These pictures are in multiple places on the Internet. They can be

found in the following places.

Frederick

Taylor

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Winslow_Taylor

Hawthorne:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawthorne_effect

|